Over the past couple of weeks I’ve had the pleasure of working with partners on training materials related to understanding the Agile Mindset. This is very much a work in progress but if you’re an Agilist you probably have an idea of how the narrative is shaping up:

“We need the organization to increase its overall business agility so that we can remain a market competitor. To do so, we need to shift how Leadership talks about value delivery and customer centricity. To do that, we need to have candid conversations. And to do that, we need psychological safety. How do we do that? Well here’s how…”

And so we’d get into the training.

But! I’m a sucker for historical context, and while not immediately relevant to what we would be reviewing, I find it useful to know why we’re doing any of this. Enter the Agile Manifesto1. It is one of the more referenced bits of Agile literature, and underpinning the manifesto are Twelve Principles of Agile Software. One of the principles is:

The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge from self-organizing teams.

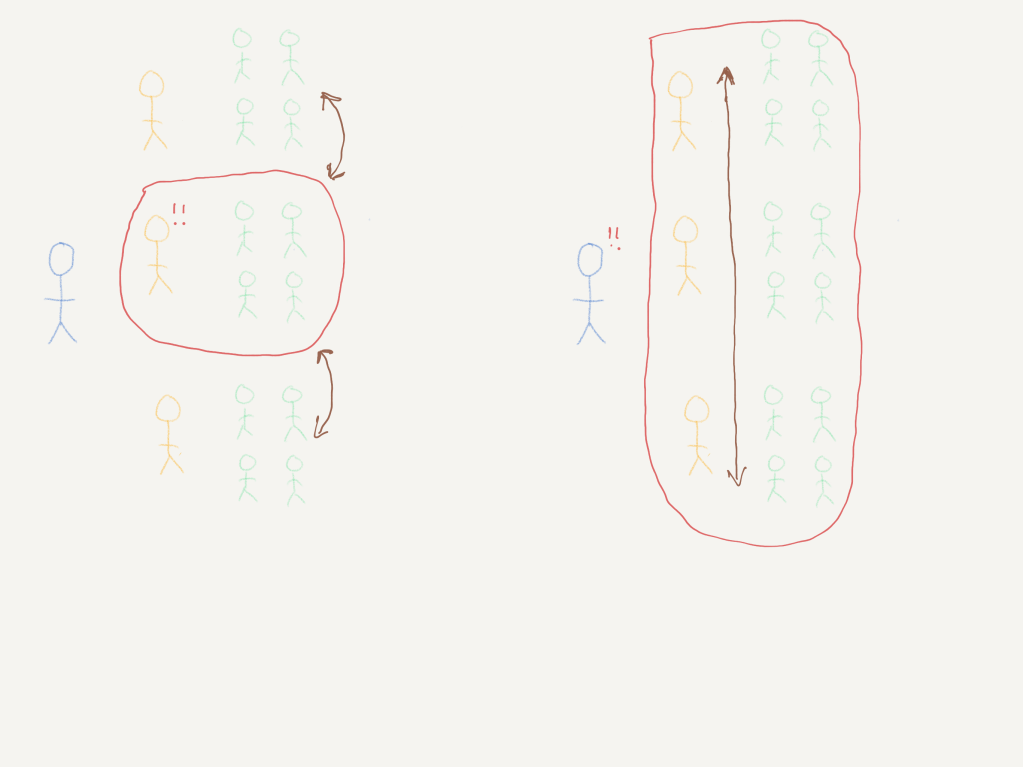

This is what people point to when they refer to self-organizing teams. It’s right there, after all. But what’s often glossed over are the words emerge and best. Complex systems – like software – don’t just appear one day. They emerge – evolve – from a set of random initial conditions and restrictions.

A good analogy to this can be found in rivers: They begin wherever water emerges from the earth. But there’s no predefined path for the water to go: It goes in the direction of gravity (down), and around obstacles (rocks, trees.) Over time, it cuts away soil and rock, and over time, we recognize a river. That river, as we see it today, can be considered the best path to deliver water from its source to any given point along the way. (Of course, with further erosion, that path will change over time, but we’ll come back to that.)

Software is much the same: Developers are given some semblance of tools, knowledge, and a goal. They then work toward achieving that goal with what they’ve got. Over time, they’ll uncover a “happy path” that requires the least amount of work to get the desired functionality. They’ll also run into obstacles and learn how not to do things. As the initial concept evolves into functioning code, we can step back and see that just like a river, the resulting system is complex, but functional in delivering value.

Unlike rivers, however, there isn’t natural erosion to guarantee the resulting code is as simple as it can be. When confronted with a decision points or obstacles, developers (read: not managers!) need to have candid conversations and fact-based discussions to determine the best way forward. They need to determine if they’ve run into a tree, or if they’re fighting gravity, or if they’re stalled because the downward slope that gave them momentum prior is suddenly a flat plain. They need to have Retrospectives.

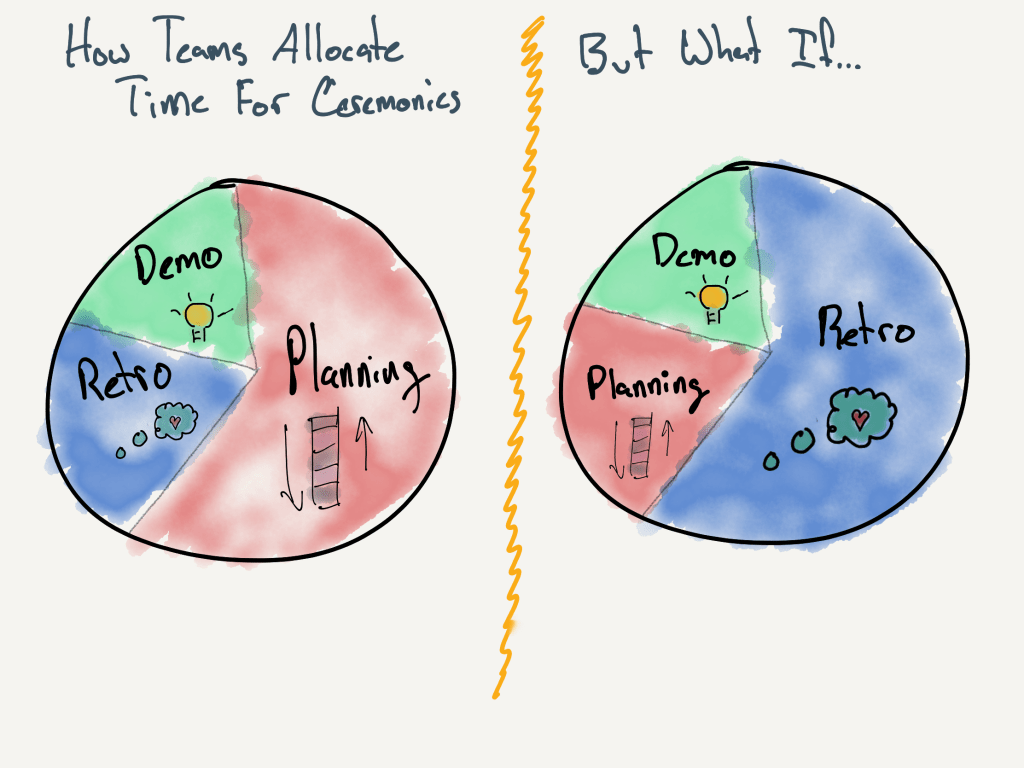

Now I’ve talked about Retrospectives before, and their criticality to a team’s ability to remain high performing. My opinion remains unchanged. But for the Retrospectives to drive the emergence of the best architecture, the best requirements, the best designs, you need the best inputs. And for the best inputs, you need candor, and for that, you need psychological safety.

The Agile Manifesto implicitly calls out the need for teams to be provided with psychological safety. But let’s make that explicit: If management expects their teams to be self-organizing and provide an organization with the best solutions, they need to create an environment of psychological safety where failures can be surfaced, learnings can be discussed, and rapid decision-making can done. To do that requires leadership, not just management. It requires a safe space for teams to thrive, and empowerment of said teams to actually do something different, not just ask for permission to do so.

Rivers aren’t beholden to management: They go wherever it makes sense for them to go. If you want something as efficient to occur on your teams, empower them, and charge them with taking action on issues they’ve uncovered. Be a leader. Provide the space and time for them to discuss these issues as frequently as make sense – maybe it’s weekly, maybe it’s monthly. Establish a structure for good, healthy Retrospectives to occur.

If you want the best possible outcomes for your customers, you’re going to need the best possible product. That can only emerge from teams who are empowered to build just that.

1 I understand the concerns folks have with a document with “Manifesto” in the title, not least of which the concern that whole thing was written by 17 dudes in skiing in Utah in 2001 – not exactly a representative group of people writing code today. But that said, it isn’t inherently bad and explains the why and how of Agile incredibly well. Its principles also trace forward to Scrum ceremonies, and Kanban philosophies are baked in. It’s a good document to reference, not a hill to die on. Proceed accordingly.